Sadness. Shock. Disbelief.

These are the emotions I felt reading a recent report by the Strategic Studies Institute of the U.S. Army War College indicating the U.S. military’s information operations (IO) and strategic communication efforts were bungled in the very places they were needed most to curb Islamist extremism. As I’ve blogged about before, it’s mindboggling that the suggested reason is large contractors hoping to make an easy buck pushing sales/marketing/attitudinal communications to enact change versus the more effective behavioral/strategic communications approach.

In this post, I am detailing three examples of what appear to be extremely counterproductive communications efforts in Afghanistan that upset and shocked me. Two are from the U.S. Army War College report, written by Dr. Steve Tatham, Great Britain’s leading military expert on strategic communication and IO, and a third is from media reports:

- Doublethink Billboard: As shown in the photo above, billboards were put up across Afghanistan extoling the virtue and loyalty of the Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF). The problem is corruption is widespread in Afghanistan and the ANSF is hardly immune. In the words of Dr. Tatham:

“[I]n a society where corruption is endemic, where successful passage through a checkpoint will almost certainly require the giving of some money, such attitudinal communication does not stack up against the pragmatic reality of life on the ground.”

The billboards remind me of George Orwell’s book 1984 and its 2 + 2 = 5 and doublethink (i.e., sometimes they are five, sometimes they are three, and sometimes they are all of them at once). While such an approach might work in a dystopian novel, it is not a fit with building a trust-based democracy in real life.

- Corruption-Covering Campaigns? Afghans citizens intensely resent the corrupt political patronage networks that replaced the Taliban. According to the Brookings Institution:

“Murder, extortion, and land theft have gone unpunished, often perpetrated by those in the government. At the same time, access to jobs, promotions, and economic rents has depended on being on good terms with the local strongman, instead of merit and hard work.”

What was done about the scourge of corruption from a communications perspective? USA Today reports IO campaigns were used to bolster corrupt Afghan officials:

“A Feb. 10, 2010, cable from then-ambassador [Karl] Eikenberry recounted a meeting between State Department and military officials with Abdul Raziq, an Afghan border police official.

Raziq, Eikenberry wrote, said he wanted to improve conditions on the Afghan-Pakistani border in Kandahar province and fight corruption. Coalition officials proposed a campaign including local radio spots, billboards and ‘if credible, the longer-term encouragement of stories in the international media on the reform of Raziq, the so-called Master of Spin.'”

A year earlier Harper’s Magazine had published an investigative piece about Raziq’s drug trafficking. While use of the term “if credible” in the excerpt above comforts me a little, the possibility of communications being used to fake reforms and prop up a drug trafficker is depressing (corruption = bad governance = fueling support for “honest” extremist governance alternatives). This example too is a bit Orwellian.

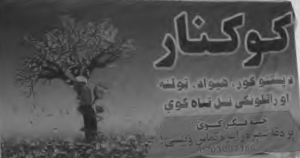

Billboard in Afghanistan reading: “Poppy. Poppy is damaging the Pashtun’s house, country, community and future generations. What do you think? Contact us on this number.”

- Doublethink Billboard II: Per the photo to the right, billboards were put up in Afghanistan reading: “Poppy. Poppy is damaging the Pashtun’s house, country, community, and future generations. What do you think? Contact us on this number.” Surely, the question toward the end was not designed with Orwellian doublethink in mind? In the words of Dr. Tatham:

“[I]t might be argued that far from ‘damaging the Pashtun’s house,’ poppy shores it up by being extremely profitable, providing a source of income to farmers that they would not be able to derive from vegetables, fruit, and wheat. Indeed, Lieutenant Colonel (Retired) John L. Cook believes that in Helmand and Kandahar: ‘The poppy is king providing, either directly or indirectly, nearly 80% of all jobs in these provinces.'”

I could write pages on how these examples are likely to harm Afghanistan’s fledging democracy and fuel extremism. I’m limiting myself, however, to five communications blunders not fully developed in my previous post on Dr. Tatham’s report (but I could go on and on about communications blunders too):

- Framed as Lies: As I have written about before, not only do you need to communicate truth (which should go without saying), you need to be very careful to avoid framing your message in a way that contradicts widespread perceptions, even if these perceptions are wrong. Perceptions lag reality, and fighting perceptions will only trick the brain into perceiving you as the liar, even when you are the one telling the truth. (Of course, using deception to trick military adversaries into surrendering, panicking, etc. are obvious life-saving exceptions, but that is another subject…).

- Create Unrealistic Expectations: Audience members who give you the benefit of the doubt will expect messages that appear to be lies to become reality at some point soon. In the examples above, many Afghan citizens would expect a virtuous ANSF and local government to be delivered in the near term along with livelihoods as lucrative as the drug trade. When something more or less promised is not delivered, disillusionment and mistrust intensify (disillusionment + mistrust = potential support for governance alternatives).

- Aimed at a Mass Homogenous Audience: A tenant of behavioral/strategic communications is targeting audience segments who are accessible, amenable to persuasion, and closely related to the survival of undesirable behaviors. The Colombia case study I recently blogged about is a great example. The examples above are unsophisticated and target a mass homogeneous audience.

- Divert Money from Potentially Powerful Policy Tweaks: A tenant of effective social marketing is changing bureaucratic processes along with public outreach to nudge adoption of desired behaviors. This approach recently became more mainstream after the best-selling book Nudge came out in 2008, but it has been being fine-tuned for decades in social marketing circles in the health and environment sectors. Getting back to the ANSF example above, if audience research revealed Afghan citizens have a low opinion of the ANSF, and, as a result, potential recruits do not join or quickly quit, implementing, enforcing, and advertising policy tweaks that make ANSF service more culturally acceptable would be a better use of limited funds. As one of my communications professors once said: “If you have a restaurant owner as a client and your client wants you to use public outreach to counter customer complaints about dirty bathrooms, strongly recommend hiring more janitors first.”

- Divert Money from Potentially More Effective Communications Channels: Billboards are not an ideal communications channel in Afghanistan for two reasons. First of all, only 28 percent of the population is literate (43 percent of men and 13 percent of women), so most Afghan citizens cannot read them. Secondly, advertising is not accepted as an everyday part of life in Afghanistan. Unlike in the heavily consumer-based societies of the West where ads are taken for granted, Afghan citizens are not as used to seeing them (or at least until not after foreign troops arrived), and an unwritten contract between marketer and potential customer does not really exist. Mobile and radio, for example, would likely be more effective and, done right, would come across less Orwellian.

Most sadly, some of these types of blunders have been known for centuries. Sun Tzu, the renowned Chinese military strategist, wrote sometime around 500 BC the following in the Art of War:

Most sadly, some of these types of blunders have been known for centuries. Sun Tzu, the renowned Chinese military strategist, wrote sometime around 500 BC the following in the Art of War:

“Engage people with what they expect; it is what they are able to discern and confirms their projections.”

Tzu recognized hearts and minds as key to military victory. Over and over, he states forms of the following:

“The supreme art of war is to subdue the enemy without fighting.”

Just imagine what could have been possible if the U.S. military and its contractors in Afghanistan had been channeling Sun Tzu vs. Orwell’s 1984?

Editor’s note: In the interests of full disclosure, some of my past and present clients and employers do anti-corruption, anti-fraud, and good governance programming on behalf of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and domestic federal agencies, so I do not see the above issues through a military lens.

Here’s a depressing but interesting 2011 update to the Harper’s Magazine “Master of Spin” story referenced above: http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2011/11/our-man-in-kandahar/308653/