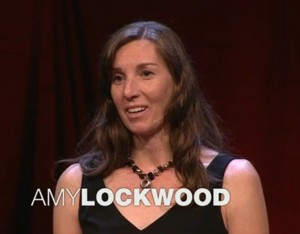

I ran across a first this week. A video of a TED Talk I didn’t find remotely jaw-dropping, informative, or inspiring. The video, my October 2011 video clip of the month, features Amy Lockwood, deputy director of Stanford’s Center for Innovation in Global Health talking about promoting condoms in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) to stop the spread of HIV/AIDS.

I ran across a first this week. A video of a TED Talk I didn’t find remotely jaw-dropping, informative, or inspiring. The video, my October 2011 video clip of the month, features Amy Lockwood, deputy director of Stanford’s Center for Innovation in Global Health talking about promoting condoms in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) to stop the spread of HIV/AIDS.

Her ingenuous idea? Something “perhaps the donor agencies had just missed out on… understanding who’s the audience.”

In other words, aid workers need to take Public Relations 101 or Marketing 101 (full disclosure: some of my previous employers do/did AIDS/HIV communications work overseas, including for the U.S. Agency for International Development [USAID], which I mention later in this post).

Lockwood’s basic premise is that because aid workers in the DRC don’t understand who their audience is, they don’t get that “aspirational messages” would better promote condoms and save more lives (i.e., Marketing 101’s “sex sells”). She also implies some may actually choose to do things that don’t work because they want to avoid upsetting prudish clients and losing their funding. Instead, she says, they rely on three ineffective categories of messaging: fear, financing, and fidelity.

After viewing her talk, I was a little stunned. Unlike every other TED video I’ve seen (I love, love, love, TED Talks), her talk was filled with misinformation, half truths, and flawed health communications concepts:

- Lockwood assumes people in the DCR are thinking about sex before they use condoms. That certainly is true in the United States. But years of brutal civil war have helped make the prevalence of rape and other sexual violence in the DRC arguably the worst in the world. In conflict zones, rebels storm villages in the dead of night, setting homes on fire, shooting men, gang-raping women, and committing other atrocities that will literally give you nightmares. According to USAID, about 25.6 percent of women who have suffered sexual violence in the DRC’s conflict areas are HIV-positive compared with 1.8 percent of women in the general population. Obviously, a significant proportion of at-risk people involved in sex acts in the DRC have terror and aggression, not sex and fun, on their minds. Marketing perpetuating the message that women are objects would likely only aggravate this nightmare.

- Just because the veiled promise of sex sells perfume, jeans, and underwear doesn’t necessarily mean the certainty of sex sells condoms. I’m doubtful of that leap. Lockwood’s four-minute talk doesn’t address any quantitative or qualitative measures she used to document the marketing superiority of generic brands with provocative packaging. She only mentions some anecdotal evidence she obtained through her personal conversations. To convince me, you would need to point to some surveys, focus groups, observational studies, etc. to support such claims. You’d also need to show the competing products were otherwise the same and price, quality, and placement/availability weren’t contributing factors.

- Fear is not typically a message major donors would use to promote condom use or most other types of desired behavior change. Fear messages often don’t work because information has little or no effect on behavior. Rather, your marketing and messages need to give people a sense of self efficacy or invoke social pressure/community norms among other things. For example, a sex worker (a critical audience segment) in the DRC who needs money to feed her family and pay her children’s school fees (school there is not free) must feel she has the power to insist her clients use condoms without risking losing them. Neither fear messages about the dangers of AIDS/HIV nor provocative packaging will give that to her. What does developing messages that address self efficacy or social pressure/community norms typically entail? Not simply knowing who your audience is. It means researching what members of each key audience segment perceive as the benefits and barriers to changing their behavior.

I personally find it hard to believe many donor agencies put funding statements on condoms as a marketing strategy. USAID, for example, does sometimes get flack for putting its logo and “this assistance is from the American people” on aid items. Condoms, however, are one the exceptions to its contract marking policy (see section 320.3.2.5). I find it odd the picture Lockwood used to demonstrate her point in her presentation says UNMIL. UNMIL, as far as I know, stands for the United Nations Mission in Liberia. Liberia is nowhere near the DRC.

I personally find it hard to believe many donor agencies put funding statements on condoms as a marketing strategy. USAID, for example, does sometimes get flack for putting its logo and “this assistance is from the American people” on aid items. Condoms, however, are one the exceptions to its contract marking policy (see section 320.3.2.5). I find it odd the picture Lockwood used to demonstrate her point in her presentation says UNMIL. UNMIL, as far as I know, stands for the United Nations Mission in Liberia. Liberia is nowhere near the DRC.- Off the communications topic but still noteworthy, Lockwood claims the DRC is the largest country in Africa. It’s not. Algeria recently became the largest country in Africa after South Sudan broke away from Sudan, which used to be the largest, in July. Perhaps she misspoke and meant sub-Saharan Africa? If not, the comment makes her appear to be a rookie.

- Also off the communications topic, Lockwood attributes the lack of life-saving drugs for HIV/AIDS victims in the DRC to “poor infrastructure.” The DRC is one of the poorest countries in the world and some bush areas are inaccessible in the rainy season. Many people in the DRC do not even have access to aspirin, refrigerators to safely store life-saving medicines and vaccines, insecticide-treated bed nets to combat malaria, or basic sterile supplies to help prevent mothers from bleeding to death in childbirth. Unfortunately, HIV/AIDS drugs are just one of a zillion unmet needs there. Brutal civil war, extreme poverty, and donor prioritization in the face of heart-breaking need, not “poor infrastructure,” are to blame.

- Perhaps most importantly, condoms are simply not available in most areas of the DRC. For this reason, it’s a little far fetched to suggest marketing or packaging are to blame for only 3 percent of the population using them.

To Lockwood’s credit, she does raise a valid concern about fidelity messages. Leaders within the Catholic Church, a strong proponent of fidelity and abstinence messages, recognized years ago married women in sub-Saharan Africa are often at a higher risk of HIV/AIDS than their single counterparts and have been debating how to better confront this challenge.

I read a post in the Freakonomics blog this week (thanks to the A View from the Cave blog) that I suspect explains why TED and Lockwood find the provocative packaging thesis so compelling. Substitute sociologist for aid worker and you’ll see what I mean:

“Sociology, of course, has its own conflicted history with common sense. For almost as long as it has existed, that is, sociology has had to confront the criticism that it has ‘discovered’ little that an intelligent person couldn’t have figured out on his or her own.

“Why is it, for example, that most social groups, from friendship circles to workplaces, are so homogeneous in terms of race, education level, and even gender? Why do some things become popular and not others? How much does the media influence society? Is more choice better or worse? Do taxes stimulate the economy?

“Social scientists have struggled with all these questions for generations, and continue to do so. Yet many people feel they could answer these questions themselves—simply by examining their own experience. Unlike for problems in physics and biology, therefore, where we need experts to tell us what is true, when the topic is human or social behavior, we’re all ‘experts,’ so we trust our own opinions at least as much as we trust those of social scientists.

“Nor is this tendency necessarily a bad reaction—any theory should be consistent with empirical reality, and in the case of social science, that reality includes everyday experience. But not everything about the social world is transparent from common sense alone—in part because not everything that seems like common sense turns out to be true, and in part because common sense is extremely good at making the world seem more orderly than it really is.”

So as you watch the video below remember those words: “Not everything that seems like common sense turns out to be true, and in part because common sense is extremely good at making [an extremely poor country like the DRC] seem more [like middle-class America] than it really is.

Your turn! Do you think more provocative packaging would stop the spread of HIV/AIDS in the DRC?

HOW TO: Engage Bonafide Critics vs. Feed the ‘Trolls’

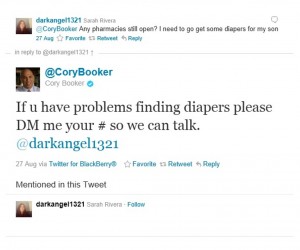

Whether you are participating in social media or not, however, these networks are giving a megaphone to all the people who are not pleased with you, at least some of the time, or have something bad to say about you. So engaging in the conversation is well worth it. A few negative comments will not undo your institution, and in fact, can be a strong opportunity for you to prove yourself and actually build goodwill with your community.

What’s the key to dealing successfully with negative feedback? Figuring out first whether you are facing “trolls” or bonafide critics.

Do Not Feed the Trolls

“Trolls” are cyber pranksters who use the Internet to have fun at someone else’s expense, typically by trying to upset them. They have no real interest in your institution but are simply online to cause problems. Internet experts argue the most effective way to discourage trolls is usually to ignore them. Trolls will not hang around and comment further if they do not get a response. That’s why many online forums warn: “Please do not feed the trolls.”

Engaging Bonafide Critics

Bonafide critics are people with specific concerns about your products or services or people who disagree with your opinions or actions (e.g., President Obama vs. the Tea Party, etc.). Unlike with trolls, you need to engage with them as quickly as you can after receiving negative feedback.

If the problems critics are complaining about are real, acknowledge your mistakes and thank them for bringing the issue to your attention, so you can take steps to right the wrongs. But never apologize and keep on making the mistake. Even if financial, policy, or strategic reasons prevent you from resolving their concerns, be sure to respond with something as simple as “Thank you for bringing this to our attention. We do things this way because….” Acknowledging complaints makes people feel heard, diffusing their anger.

If your critics’ complaints are unfounded, however, and you believe you are right, simply state the facts, so your audience can understand the difference between your position and your critics’. Then let the facts and your actions speak for themselves and move on. An overly strong defense can make you look guilty, hurting your case.

Is how you handle critics off-line different that how you would handle them online? Do you do something differently than what I suggested? Add to the knowledge by adding a comment.